The City of New York at the ice

The City of New York at the ice

First Byrd Antarctic Expedition

Having flown to the North Pole and over the Atlantic Byrd set his sights to fly to the South Pole. In 1929 he launched the largest and most expensive expedition to Antarctica that had ever been attempted. The goals of the of the first Byrd Antarctic Expedition I (BAE I) were twofold. First, to make the first flight to the South Pole.

Second, to serve science by bringing experts to study meteorology, geology, zoology, geography, aerial photography and other disciplines. BAE I was also

equipped to be in radio contact with the outside world.

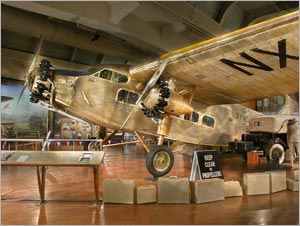

Byrd assembled two ships, the City of New York and the Eleanor Bolling, and they embarked for Antarctica in 1928. Then there were 95 sled dogs and 650 tons of supplies. The crown jewels of the expedition were the three airplanes. The big Ford tri-motor "Floyd Bennett" which was to make the South Pole flight was named the Floyd Bennett after Byrd’s close friend and North Pole pilot who was injured in the America crash and who subsequently contracted pneumonia and died. Then there was a single engine Fokker Super Universal named the Virginia and a single engine Fairchild named the Stars and Stripes.

Having flown to the North Pole and over the Atlantic Byrd set his sights to fly to the South Pole. In 1929 he launched the largest and most expensive expedition to Antarctica that had ever been attempted. The goals of the of the first Byrd Antarctic Expedition I (BAE I) were twofold. First, to make the first flight to the South Pole.

Second, to serve science by bringing experts to study meteorology, geology, zoology, geography, aerial photography and other disciplines. BAE I was also

equipped to be in radio contact with the outside world.

Byrd assembled two ships, the City of New York and the Eleanor Bolling, and they embarked for Antarctica in 1928. Then there were 95 sled dogs and 650 tons of supplies. The crown jewels of the expedition were the three airplanes. The big Ford tri-motor "Floyd Bennett" which was to make the South Pole flight was named the Floyd Bennett after Byrd’s close friend and North Pole pilot who was injured in the America crash and who subsequently contracted pneumonia and died. Then there was a single engine Fokker Super Universal named the Virginia and a single engine Fairchild named the Stars and Stripes.

Little America on Ross Ice Shelf

Little America on Ross Ice Shelf

In early 1929 Byrd set up his base camp called Little America four miles from edge of the Ross Ice Shelf on the Bay of Whales. forty two men (all volunteers) would "winter over" enduring several months of darkness. The South Pole flight was planned for November after the sun reappeared in the spring. Little America was only four miles from Framheim established by Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen’s in 1911 when he used sled dogs to be first to reach the South Pole in December of that year.

In March, 1929, Byrd sent his geologist Larry Gould along with pilot Bernt Balchen and radioman Harold June out in the Fokker to the Rockefeller Mountains for some geological studies. The men pitched their tent, tied the plane down, but a blizzard roared in and ripped the Fokker from its moorings and sent it sailing through the air for about a mile. It came crashing down on a frozen lake destroying the radio, so they could not communicate with Little America about the wreck. Several days later Byrd and pilot Dean Smith flew out in the Stars and Stripes, located the marooned men, and flew everyone back to Little America.

In March, 1929, Byrd sent his geologist Larry Gould along with pilot Bernt Balchen and radioman Harold June out in the Fokker to the Rockefeller Mountains for some geological studies. The men pitched their tent, tied the plane down, but a blizzard roared in and ripped the Fokker from its moorings and sent it sailing through the air for about a mile. It came crashing down on a frozen lake destroying the radio, so they could not communicate with Little America about the wreck. Several days later Byrd and pilot Dean Smith flew out in the Stars and Stripes, located the marooned men, and flew everyone back to Little America.

In November after winter passed it was time to prepare the Ford tri-motor for the South Pole flight. Byrd insisted on taking photographer Captain Ashley McKinley and his several hundred pounds of bulky photographic equipment. All this weight meant the Floyd Bennett could not fly non-stop from Little America to the Pole and back again so Byrd flew out to the base of the Transantarctic Mountains ahead of time and established a fuel cache so they could refuel on their flight back from the Pole.

November 29, 1929, dawned crystal clear. The Floyd Bennett was loaded with extra fuel in five gallon containers, 750 pounds of emergency food in case they went down, survival gear, and Captain McKinley’s photographic equipment. The pilot Bern Balchen, navigator Byrd, photographer McKinley, and radioman Harold June climbed aboard. It was estimated the entire plane weighed 15,000

pounds.

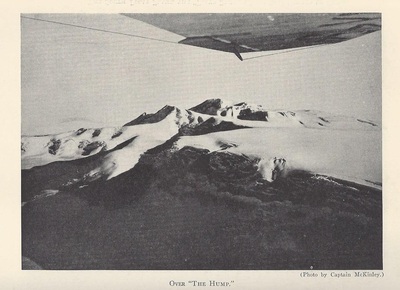

The flight over the flat expanse of the Ross Ice Shelf went well but they had to fly over the Transantarctic Mountains looming ahead of them with peaks exceeding 10,000 feet. As they approached Balchen shouted that the plane wouldn’t go any higher and they had to shed some weight to gain altitude to clear the range. Should they dump fuel or emergency supplies? Byrd didn’t think twice, out went 250 pounds of food. Captain McKinley took a picture of the plane barely clearing

‘The Hump” as they flew over the Liv Glacier at 90 mph.

November 29, 1929, dawned crystal clear. The Floyd Bennett was loaded with extra fuel in five gallon containers, 750 pounds of emergency food in case they went down, survival gear, and Captain McKinley’s photographic equipment. The pilot Bern Balchen, navigator Byrd, photographer McKinley, and radioman Harold June climbed aboard. It was estimated the entire plane weighed 15,000

pounds.

The flight over the flat expanse of the Ross Ice Shelf went well but they had to fly over the Transantarctic Mountains looming ahead of them with peaks exceeding 10,000 feet. As they approached Balchen shouted that the plane wouldn’t go any higher and they had to shed some weight to gain altitude to clear the range. Should they dump fuel or emergency supplies? Byrd didn’t think twice, out went 250 pounds of food. Captain McKinley took a picture of the plane barely clearing

‘The Hump” as they flew over the Liv Glacier at 90 mph.

Once they arrived over the flat Polar Plateau it was smooth sailing. Incredibly they were flying at 11,000 feet elevation but the ice beneath them was so thick they were only 1,500 feet over the surface! When they reached the South Pole Byrd took several sextant observations to confirm the fact, Balchen flew a circle around the imaginary point, and Byrd dropped an American flag weighed down with a stone from his good friend Floyd Bennett’s grave. Captain McKinley captured the event on film.

The flight back to Little America was easy. The Ford tri-motor was much lighter, they had a tail wind, and Balchen opened up the throttles to 125 mph. Once back over the Transantarctic Mountains they landed at the fuel cache, gassed up, and arrived back at Little America after an 18 hour flight.

Black and white clips of BAE I here (captions with music):

The flight back to Little America was easy. The Ford tri-motor was much lighter, they had a tail wind, and Balchen opened up the throttles to 125 mph. Once back over the Transantarctic Mountains they landed at the fuel cache, gassed up, and arrived back at Little America after an 18 hour flight.

Black and white clips of BAE I here (captions with music):

On his return to the United States Byrd was given a hero’s welcome. Not only had he flown to the South Pole but also mapped vast reaches of unknown territory and advanced geological, magnetic, meteorological knowledge about Antarctica. Congress promoted Byrd to Rear Admiral and he was given another tickertape parade in New York.

National Science Foundation commemorates the 50th anniversary

of Byrd's flight to the South Pole, November 29, 1979

of Byrd's flight to the South Pole, November 29, 1979